HAR GHAR JAL

In the Union Budget 2019, GoI launched ‘HarGharJal’, a mission mode campaign aimed at providing FHTCs (Functional House Tap Connections) to every rural household by 2024. The programme focuses on service delivery at the household level through regular water supply in adequate quantity and of prescribed quality. This necessitates the use of modern technology in planning and implementation of water supply schemes, development of water sources, treatment, and supply of water.

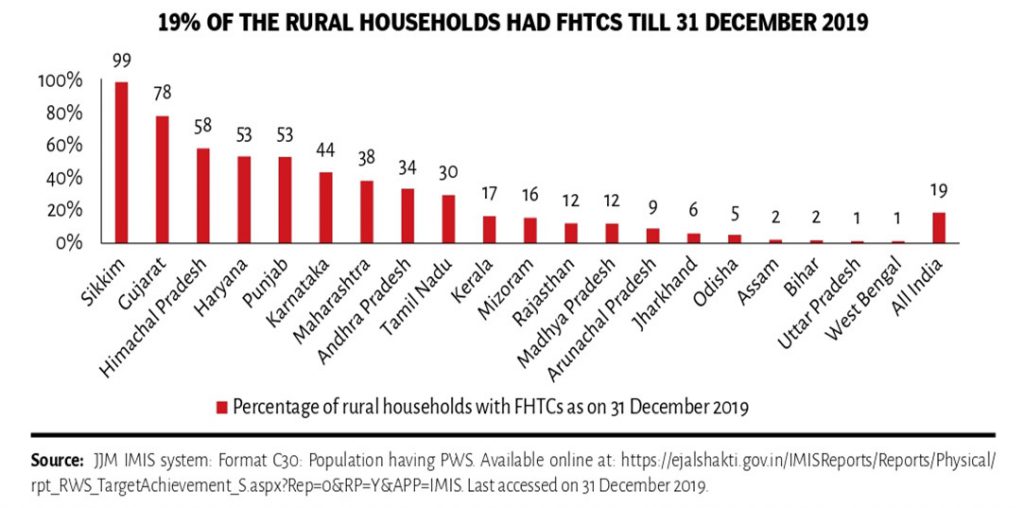

As on 31 December 2019, 19 per cent of the rural population had been provided with FHTCs. While 13 states and UTs had a coverage of less than 10 per cent, 3 states and UTs had a coverage of over 60 per cent.

States with the highest coverage included Sikkim (99 per cent), Gujarat (78 per cent), and Himachal Pradesh (58 per cent). States with coverage of less than 10 per cent included Arunachal Pradesh (9 per cent), Jharkhand (6 per cent), Odisha (5 per cent), Assam (2 per cent), Bihar (2 per cent), Uttar Pradesh (1 per cent), and West Bengal (1 per cent).

AS ON 31 DECEMBER 2019, 19% OF THE RURAL HOUSEHOLDS HAD FHTC (Functional Household Tap Connection)

The Case of India

The “Swachh Bharat” or Clean India mission for the first time put sanitation at the centrestage drawing political priority from the highest level. Backed by a cumulative funding of 20 Billion USD over 5 years (2014-19) and a well thought behaviour change campaign driven by narratives from all social levels, the mission was achieved in making the country open defecation free. However, there two major things that Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) did not fully focus on is the urban component and rest of the sanitation value chain. SBM was largely rural focused, building 110 million toilets lifting 600 million people from practicing open defecation. Similarly, the focus was on toilet provision, and not on managing the entire value chain from source to treatment. This results in that fact that only 33% of urban wastewater in India is treated.

On the other hand, older policies such as the National Urban Sanitation Policy (NUSP) and newer schemes such as the ‘AMRUT’, focus on dealing with the same challenge of providing 100% safely managed urban sanitation. The NUSP from 2008, is a policy that is well aligned with the CWIS principles, and in fact puts urban sanitation planning in the limelight. The City Sanitation Plan (CSP) that NUSP recommends is a comprehensive planning approach that is cross-sectoral and aims to be the go-to document for city managers in all aspects covering sanitation (including water supply, solid waste and storm water drainage). Despite of CSP being the core instrument of implementing the vision of the NUSP, the support of international agencies such as GIZ and World Bank in implementation and in developing a practitioner’s framework in operationalizingthe CSP, it is still considered at large a failure in delivering the impact it promised.

Water is one of the most essential requirements of life. Assured availability of potable water is vital for human development. India is home to 18% of global human population and 15% of global livestock population. However, it has only 2% land mass and 4% of global freshwater resources. As per estimates2; in 1951, per capita annual freshwater availability was 5,177 cubic meters which came down to 1,545 cubic meters in 2011. It is estimated that in 2019, it is about 1,368 cubic meters which is likely to further go down to 1,293 cubic meters in 2025. If present trend continues, in 2050, freshwater availability is likely to decline to 1,140 cubic meters.

Copyright © 2021

Design & Developed by Inventeam Solutions Pvt. Ltd.